Focus on European power reserves: part 1 - FCR

A first post on the European power reserves exploring FCR, the Frequency Containment Reserves, previously called primary reserves, with a focus on prices.

Power reserves are an essential part of the electricity sector as they ensure the stable operations of our power grids. The increasing integration of renewables, particularly solar energy, significantly impacts power reserves. Therefore, it's essential to give due attention to these aspects. This is why I've decided to focus some posts on power reserves in Europe, a topic that is more complex and specialized than wholesale markets, which I have explored in several posts already.

This post will focus on the fastest power reserves in Continental Europe, known as Frequency Containment Reserves (FCR), formerly called primary reserves. I will explain some of the technical details of these reserves and how they are currently procured across a large bloc of European countries. As usual on this Substack, I will also present insights on the prices of these specific reserves and link them with the surge of renewables, especially solar. Let’s dive in.

The different power reserves in Continental Europe

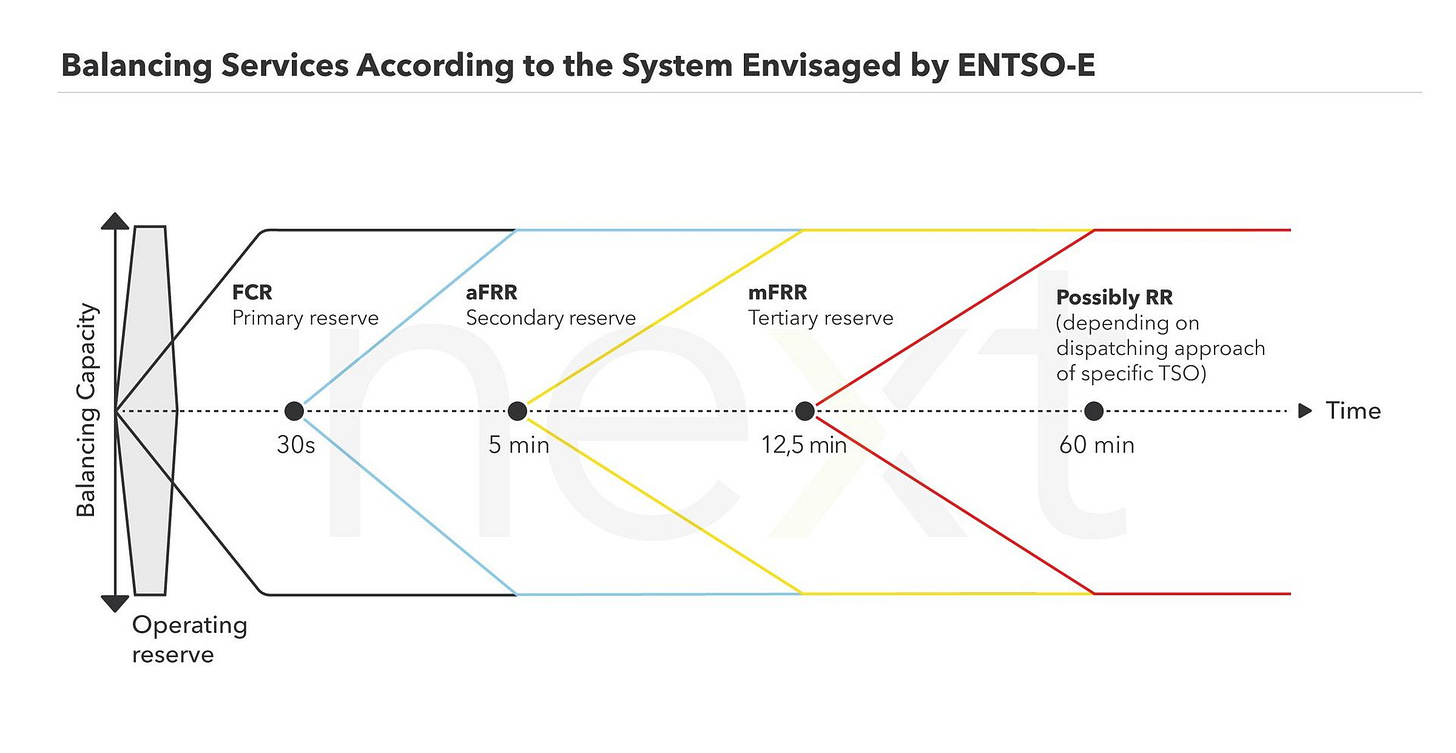

Electricity consumption and generation must always be balanced. To maintain this equilibrium, grid operators utilize various power reserves, ranging from the fastest (FCR) to slower reserves. The graphic below illustrates the different types of power reserves used in Europe.

It is not my objective to review all the details of the different power reserves. For more information and context, you can consult the interesting pages of Next-Kraftwerke: FCR, aFRR, or the Electricity Balancing Guideline (EBGL).

FCR procurement

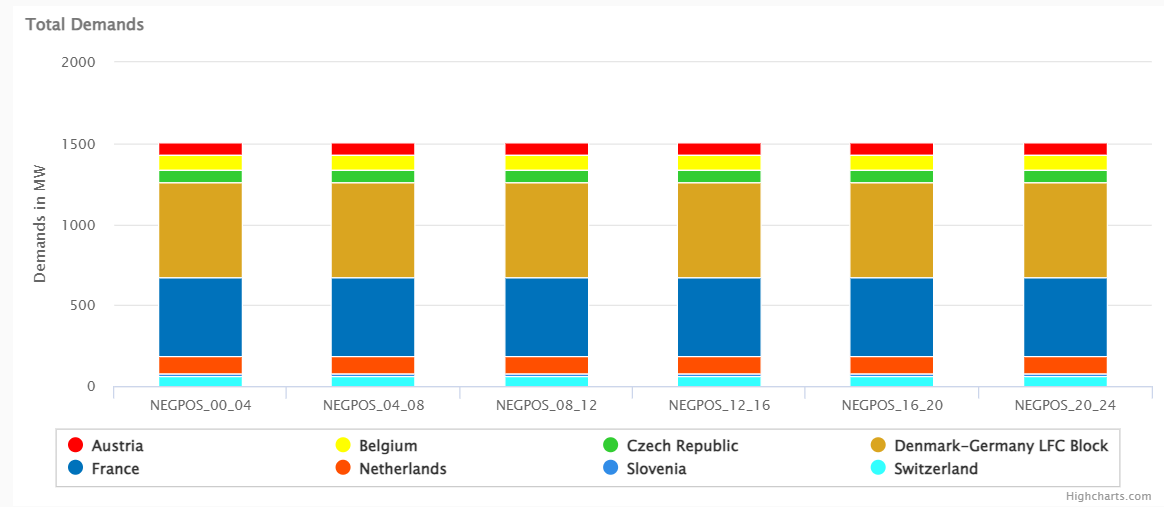

To describe the evolution of FCR prices, it's essential to explain some specificities of FCR procurement1. Currently, nine European countries organize a daily joint tender to procure FCR, amounting to 1,503 MW of the 3,000 MW required for continental Europe. These countries are Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Slovenia, and Switzerland.

The total demand per country is based on its relative size (e.g., Belgium must procure 93 MW in 2024, while France must procure 486 MW). Each country must procure at least 30% of its demand locally. For larger countries, total export capacity is restricted as follows for 2024: 145 MW in France, 176 MW in the Denmark/Germany block, and 100 MW for all other countries combined.

FCR operates as a capacity-only market, meaning that only the availability of the reserves is remunerated, not their activation2. Procurement occurs daily in blocks of four hours, resulting in six auctions per day. The blocks are as follows: 0 to 4 AM, 4 to 8 AM, and so on.

It should be noted that in some countries, FCR is not subject to a market mechanism. Instead, certain transmission system operators oblige some large producers to provide these reserves on a compulsory basis.

In case FCR is procured through a market mechanism, the cost would in general be included in the transmission tariff. If some producers must provide it without remuneration, the FCR cost would be supported by them3.

Market trends since 2023

The tables below present market trends since 2023. On the left side, you'll find the average price per MW for a four-hour block, broken down by month. On the right side, you'll see the average position of each country, indicating whether they are net exporters or importers of FCR to neighboring countries. My observations are as follows4:

FCR constitutes a very small fraction of the total cost of providing power. For instance, 3,000 MW valued at the average German FCR price in 2023 amounts to approximately €328 million per year. In comparison, the total electricity consumption in the EU was 2,696 TWh in 2023. At a valuation of €80 per MWh, this equates to €216 billion, or 600 times more. Even considering the higher Belgian prices at the end of 2023, the total market value of FCR remains under 1% of the economic valuation of electricity consumption5.

There was one exceptional price event observed in the Netherlands in November 2023: for one block, the price soared to €77,777 per MW, which is over a thousand times the average price and nearly equivalent to one year's remuneration in just four hours.

An asset providing 1 MW of FCR in Germany, assuming 100% availability, would have earned approximately €112,000 in 2023.

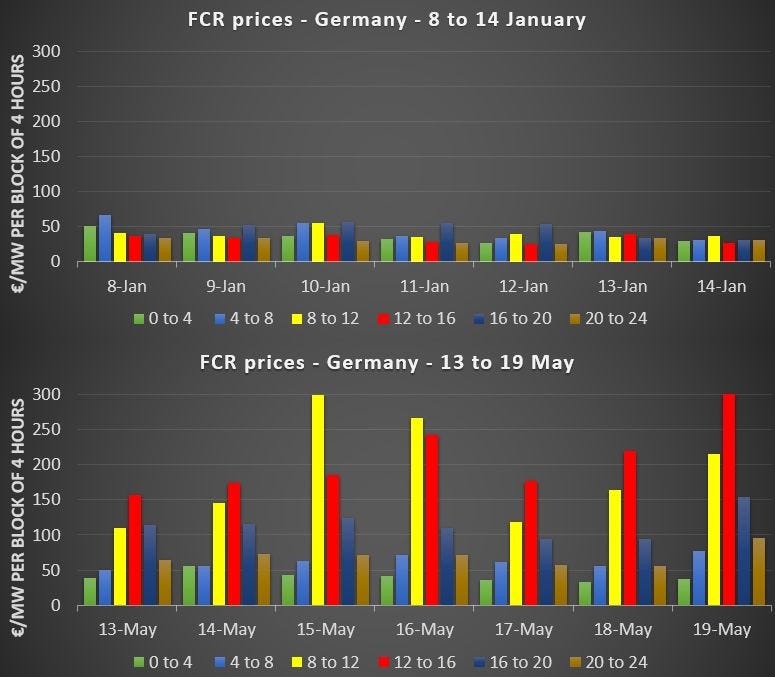

We observe a solar effect where prices are higher for the 12 to 16 block. This is due to a lack of flexible assets during this period and increased remuneration for flexibility. This trend is even more evident when comparing a winter week to a spring week (see below).

France has very low FCR prices and exports close to its maximum capacity, especially since 2024.

Belgium, in contrast, almost always operates near its maximum import capacity.

Comparison between a winter and a spring week - the impact of solar

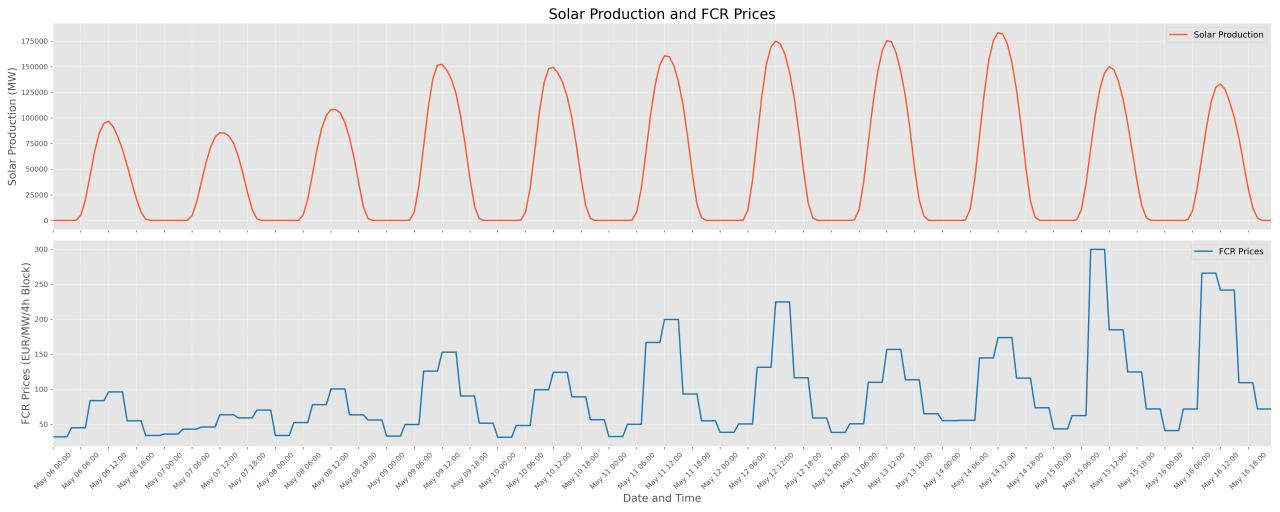

When we look at a particular week, we can clearly observe the impact of solar on prices. Hereunder are the FCR prices for Germany in two very different weeks: one in winter with low renewables and one in spring with high solar generation.

The following graph presents the solar generation in Germany compared to FCR prices for several days. We can observe a clear correlation between them.

This effect is also observed in other market segments of the power reserves such as the capacity prices of aFRR, suggesting a propagation of the prices across market segments when flexibility is lacking.

Future trends - the rise of batteries

Predicting future price trends is always challenging. However, one important development concerning power reserves is the arrival of batteries. In Germany, many large-scale batteries (LLS) are already participating in the provision of FCR. From a report of March 2023:

“Ancillary services (in operation: 750 MWh / 685 MW) are still leading. Until 2019, LSS have been built almost exclusively for the provision of frequency containment reserve (FCR) … During this time, however, the prices for FCR initially dropped significantly, primarily due to the increasing saturation of the market volume by battery storage, which is why economic operation became more difficult and the market declined until 2021 but increased in 2022 again. As of January 2023, the German FCR market is 570 MW, while already 630 MW of LSS are officially prequalified to provide FCR.”

Large-scale batteries are indeed playing a pivotal role in shaping the evolution of FCR prices. However, their presence doesn't necessarily guarantee price stability. Indeed, flexibility providers will actively pursue opportunities to maximize revenues. In scenarios where flexibility is constrained, such as during peak solar periods, prices across various flexibility-related markets may be impacted. This could include increased pressure on intraday prices, aFRR and mFRR capacity prices, energy activation prices, as well as imbalance prices. Market players, including battery operators, are likely to gravitate towards the most profitable markets, which could result in price dynamics propagating across different market segments.

Therefore, as the number of flexibility providers increases in order to face higher penetration of renewables, the market for FCR, but more broadly for power reserves in general, is likely to fluctuate between an abundance of flexibility options (when renewables are not producing much, traditional flexibility providers could still be active) to relative scarcity. In particular, I believe that solar is likely to have more impact than wind in my opinion, due to its much higher concentration6 and some of the current support schemes making solar in Western and Central Europe inflexible7.

A last word

If you like my Substack, do not hesitate to forward it to your friends and colleagues. Furthermore, I am always enthusiastic about discussing energy and markets with peers, so do not hesitate to contact me by email (julien.jomaux@gmail.com) or via LinkedIn (where I post more frequently).

The transmission system operators are responsible for ensuring a sufficient amount of FCR in their electricity grid.

The activation of FCR is based on the grid frequency, fluctuating around 50 Hz, which is the same inside a synchronous zone.

Interestingly, these producers would have to compensate for this cost by slightly increasing the cost of the energy they deliver, which could be interpreted as an “unfair disadvantage’ compared to countries where FCR is procured separately.

Contact me if you wish to receive data for the remaining countries or additional insights on FCR prices. The post would have been too long to incorporate all the data.

Only considering the energy value and not the cost to deliver this energy (transmission and distribution cost).

I wonder if these pricing effects for flexible load will make hydrogen more attractive in a world where natural gas peakers are increasingly disincentivized.

We may have to come up with alternative plans when the penny finally drops that putting intermittent providers (sun and wind) on the grid will not work past a point where there is not enough reliable power to meet demand, and you get the British and German descent into recession.

https://newcatallaxy.blog/2023/07/11/approaching-the-tipping-point/

https://www.flickerpower.com/index.php/search/categories/general/the-energy-crisis-how-we-got-here-and-how-to-move-on