How cheap will solar projects get?

Cost of solar projects is expected to decrease by a third in a decade - still impressive but much less than the previous decade

We have all heard that solar has decreased a lot in recent years. But by how much? And more importantly, will it continue? And could it beat the cannibalization effect (see the posts on that here: 1 and 2)? Let’s dig in.

An amazing decrease

The total cost of solar projects has experienced an extreme decrease since the start of the technology a few decades ago. In the Renewable power generation costs 2021 of IRENA, we can observe a decrease of 82% from 2010 to 2021 for the average total system cost (from 4808 to 883 US$/kW).

The main driver for the project cost a decade ago was the module price. The study International Technology Roadmap for Photovoltaic presents interesting data on historical prices and future projections.

The learning curve for solar modules has been steady, improving by almost 40% for each doubling of solar shipments from 2006 to 2022. In March 2022, we reach the global value of 1 TWp and the average module price in 2022 was 0.23 $US/Wp.

The learning is always a combination of two factors: an efficiency improvement and a continued cost reduction per piece. It should be noted that the per-piece learning stopped between 2019 and 2021. In addition, efficiency improvement is starting to be complicated without cost increase.

This cost decrease for modules and consequently for solar projects allowed solar to be the fastest energy source deployed1. This incredibly rapid rollout is likely to continue for the coming years as we have developed in a post earlier.

So, solar projects and solar modules have seen their cost drop during the past decade. But what about the next one? Could the cost of a solar project still go much lower?

Cost prospects

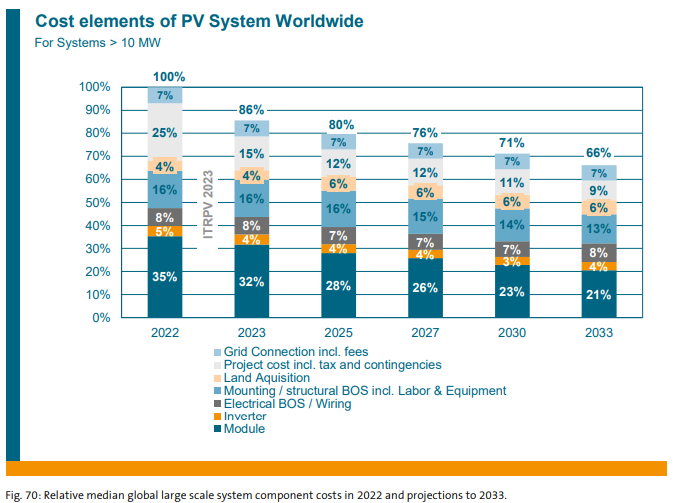

The following graph presents the prospects for the cost elements of large solar systems (larger than 10 MW). It is expected that the cost will “only” decrease by a third in ten years. This decrease is mainly driven by two elements: module prices (40% decrease) and project costs (64% decrease).

Concerning the module prices, it means somehow the end of the incredible decrease of the last decades. Module prices were in 2022 at 0.23 US$/Wp and we can still expect some diminution but it would be rather limited compared to the historical price drop2. Actually, even if the module price gets to zero, the total project cost will be cut by a third only. With the expansion of solar, the industrial process of module manufacturing seems to be coming to a mature state where improvements will only be marginal in the coming years. Actually, we might even face a supply glut and we observe recently a drop in the shares of solar manufacturers.

The second element expected to decrease is the project costs, meaning that the margins are likely to be squeezed for project developers. Such improvement will be made possible by the increased competition for solar developers. The use of innovative techniques such as advanced machinery for panel installation would also decrease the cost in places where labor is an important cost factor.

Oversizing will be the new norm

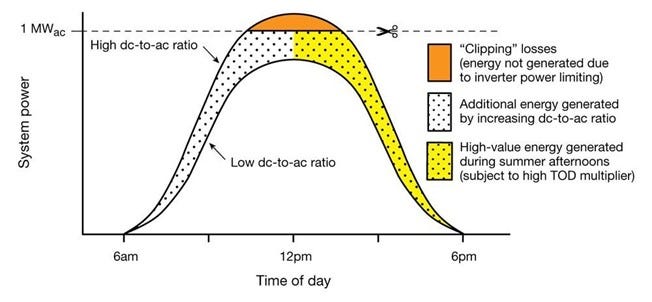

As the cost of modules decreases faster than the cost of transmitting the power (inverters, powerlines, transformers), oversizing would become the new norm. Oversizing refers to the fact that the installed capacity of solar modules (the direct current - DC) would be higher than the inverter capacity (the alternative current - AC).

The clipped energy3, i.e. the energy that is lost due to the smaller inverter capacity compared to the solar panels, might be financially compensated by the cheaper equipment to transmit power4. Furthermore, the clipped energy would probably be not worth much as it is produced during the peak of solar generation.

LCOE is up for the first time

In their latest LCOE5 report, Lazard noticed for the first time an increase in the average cost for solar, driven by various factors including the rise in financing costs. Nevertheless, it is expected to go down again in the coming years.

LCOE for the coming decade

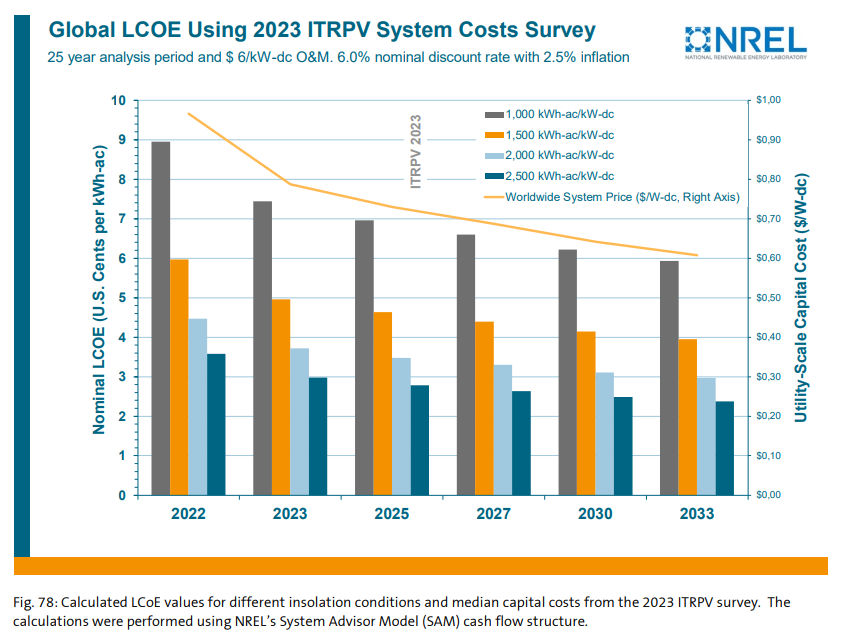

What can we expect concerning the LCOE for solar projects in Europe? This will depend on the location of the solar project, which determines the insolation conditions. The following graph represents the LCOE for the next decade for four different insolation conditions, measured in kWh-ac produced per kW installed.

The insolation in Europe is around 1000 kWh/kWp for the Northern part of Europe, excluding the UK and the Nordic countries (even lower). Southern Europe, especially the Iberian peninsula, has higher insolation, up to 1700 kWh/kWp. Considering insolation of 1000 kWh/kWp (Germany, North of France, Benelux, Poland, Republic Czech Republic), the LCOE of large projects would be in the range of 0.06 to 0.07 $US/kWh for the coming decade. Southern Europe benefits from better insolation conditions, with up to 70% improvement.

This assessment is aligned with the latest auctions in Germany where the utility-scale solar projects had an average price of 77 $US/MWh, corresponding to the average LCOE price of 2023 for an insolation of 1000 kWh/kWp.

A race between cost decrease and cannibalization effect

As we described in our previous post on solar cannibalization, the captured value of solar is decreasing with its penetration. By using the graph from this study, we can draw lines of the LCOE for Northern Europe and for Southern Europe for this coming decade.

As we discussed in our piece on CfD, we might face a situation in the coming years where the strike price of this support mechanism, which lies in a similar range to the LCOE in theory, would be higher than the captured prices. It is likely that we will arrive at such a situation within the coming decade, even though there are many unknowns6.

In a nutshell

Solar has experienced one of the most incredible price declines of any physical goods. We are now at a high level of maturity in the manufacturing of modules as well as in solar project developments, resulting in most probably only incremental changes. This will translate into a one-third reduction of LCOE for large solar projects in one decade, a good achievement but not as impressive as the last decade.

So, could there be a limit to solar expansion due to its economics? Maybe yes, even though it would depend on the cost of other elements (batteries, electrolyzers, flexibility of electric vehicles, etc.). That’s a topic for another post, except if you have Twitter.

After reaching the milestone of 1 EJ (exajoule), equal to 277.8 TWh, or slightly less than the electricity consumption of Italy.

A module cost today only one percent of a module three decades ago.

We could also consider that clipped energy is the equivalent of local curtailed energy.

In addition, the grid might be constrained to only accept a certain maximal power.

Future prices depend on a broad range of variables such as commodity prices (gas, coal), technology development, state of the transmission grid, regulatory changes, etc.

"the LCOE of large projects would be in the range of 7 to 6 $US/kWh for the coming decade"

That would be very, very expensive! Do you mean 6 to 7 $Cent?